Inter-contract invocations

In this guide, we will look into contract interactions on Tezos. We will provide examples of how one contract can invoke and create other contracts on the same chain. We will also describe the execution model Tezos contracts live in and see how it is different from a more conventional "direct calls" model.

Internal operations

When you make a transaction to a contract, this contract may, in turn, emit other operations. Those operations are called "internal". There are three kinds of internal operations:

- Transaction – an operation that transfers value and, if the callee is an originated contract, executes the code of the callee.

- Origination – creates a new smart contract.

- Delegation – sets a delegate for the current contract.

We will mainly focus on internal transactions, as this is the most common type of internal operations. We will also show how contracts can originate other contracts.

A note on complexity

Usually, you do not want to have overly-complex contract interactions when you develop your Tezos contracts. There are several reasons for this:

- Transactions between contracts are expensive. Tezos bakers need to fetch the callee from the context (this is how internal blockchain storage is called in Tezos), deserialise and type-check it, then perform the requested operation and store the result. Among these actions, code execution is the cheapest one in terms of gas.

- Transactions between contracts are hard and error-prone. When you split your business logic across several contracts, you need to think of how these contracts interact. This may cause unforeseen vulnerabilities if you do not give it enough attention.

- Tezos most probably has other means to achieve what you want. Lambdas make it possible to alter the behaviour of the contract after origination, new cryptographic primitives get introduced via protocol upgrades, separation of concerns can be achieved by splitting your business logic into LIGO modules that will eventually get compiled into a single contract, etc.

However, there are legit reasons for using internal operations, including the following:

- You communicate with an external entity, e.g., transfer a third-party FA2 token.

- You develop a universal caller contract, e.g., a multisig contract.

- You implement a standard that explicitly forbids you to extend the functionality.

Internal transactions in LIGO

The simplest example of an internal transaction is sending Tez to a contract. Note that in Tezos, implicit accounts owned by people holding private keys are contracts as well. Implicit accounts have no code and accept unit as the parameter. Consider the following code snippet:

It accepts a destination address as the parameter. Then we need to check whether the address points to a contract that accepts a unit. We do this with Tezos.get_contract_opt. This function returns Some (value) if the contract exists and the parameter type is correct. Otherwise, it returns None. In case it is None, we fail with an error, otherwise we use Tezos.transaction to forge the internal transaction to the destination contract.

Note: since

Tezos.transactionis called with unit as its first argument, LIGO infer thatdestination_addrhas to point to a contract that accepts unit

Let us also examine a contract that stores the address of another contract and passes an argument to it. Here is how this "proxy" can look like:

To call a contract, we need to add a type annotation : int contract

option for Tezos.get_contract_opt. LIGO knows that

Tezos.get_contract_opt returns a contract option but at the time

of type inference it does not know that the callee accepts an

int. In this case, we expect the callee to accept an int. Such a

callee can be implemented like this:

But what if we want to make a transaction to a contract but do not know the full type of its parameter? For example, we may know that some contract accepts Add 5 as its parameter, but we do not know what other entrypoints are there.

LIGO compiler generates the following Michelson type for the parameter of this contract:

The type got transformed to an annotated tree of Michelson union types (denoted with or typeA typeB). The annotations (%add, %multiply, etc.) here represent entrypoints – a construct Tezos has special support for.

In Tezos, we are not required to provide the full type of the contract parameter if we specify an entrypoint. In this case, we just need to know the type of the entrypoint parameter – in case of %add, it is an int – not the full type.

To specify an entrypoint, we can use Tezos.get_entrypoint_opt instead of Tezos.get_contract_opt. It accepts an extra argument with an entrypoint name:

To get the entrypoint names from parameter constructors, you should make the first letters lowercase and prepend a percent sign: Add -> %add, CallThePolice -> %callThePolice. LIGO does this transformation internally when it compiles your code into Michelson.

Entrypoints are especially useful for standardisation. For example, FA2 token standard does not force the contracts to have some specific parameter type – it would be too limiting for tokens that want to have additional functionality. Instead, the standard requires the tokens to have some predefined set of entrypoints, and other contracts may expect these entrypoints to be present in FA2-compliant tokens.

Interoperability and standards compliance

There are several high-level languages for Tezos, and you should not expect that all the contracts you interact with are written in LIGO.

Internally, Tezos stores and operates on contracts in Michelson. Currently, Michelson does not support record and variant types of arbitrary length natively. It only has pair a b and or a b, each containing just two type parameters.

However, other languages may use a different representation. For example, they can use a right-hand comb:

It is not a problem for top-level parameter types: we can expect the callers to specify an entrypoint. But if we pass structures and values of variant types as entrypoint arguments, we need to make sure their internal representation is the same.

If you interact with other contracts, or expect other contracts to interact with your contract, we strongly advise you to consider using special types and annotations described in the Interoperability section of the documentation.

Execution order

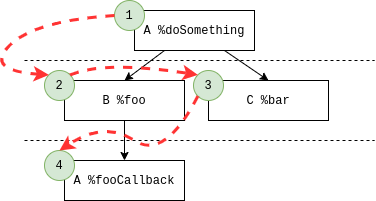

When you emit an internal operation, Tezos puts it into the internal operations queue. Here is how this queue looks like when you have one contract that emits two internal operations:

| Current call | Queue before | Queue after |

|---|---|---|

A %doSomething | [] | [B %foo, C %bar] |

B %foo | [C %bar] | [C %bar] |

C %bar | [] | [] |

Now imagine that B %foo emits another operation, e.g. it calls back to A %fooCallback. Tezos will put this internal operation to the end of the queue:

| Current call | Queue before | Queue after |

|---|---|---|

A %doSomething | [] | [B %foo, C %bar] |

B %foo | [C %bar] | [C %bar, A %fooCallback] |

C %bar | [A %fooCallback] | [A %fooCallback] |

A %fooCallback | [] | [] |

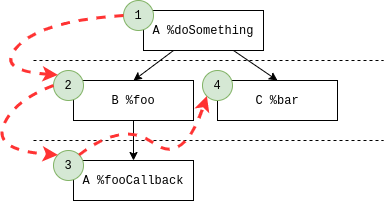

Notice how this callback gets executed after C %bar. If we construct a tree of internal operations, such queuing would be analogous to a breadth-first search (BFS):

This BFS execution order is very different from Ethereum's direct synchronous method calls, which are analogous to depth-first search. Here is how the transactions would be ordered in Ethereum:

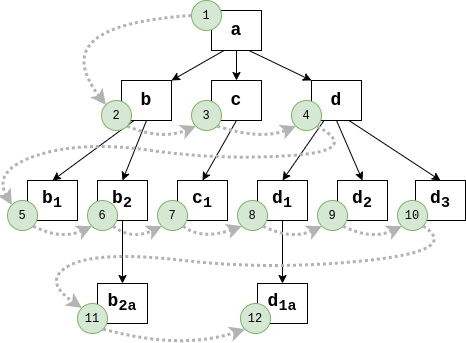

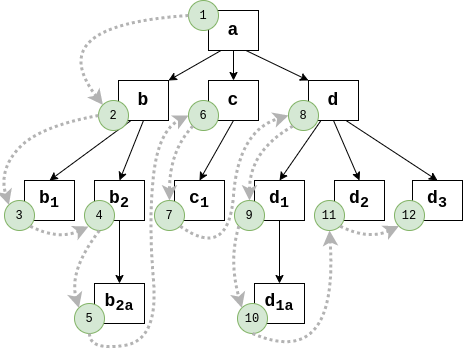

Here is a more complex scenario featuring a graph of 12 different operations. We omit the contract and entrypoint names and use lowercase letters and numbers to identify operations.

- BFS order (Tezos):

- DFS order (Ethereum):

In practice, you should always bear in mind that the internal operations are queued and not executed immediately. It means that:

- There is no guarantee that there would be no operations in between the current transaction and an emitted operation (e.g., on the BFS graph above,

b2emitsb2a, but 4 operations are executed in between these two). - If you emit a sequence of operations, they will be executed one after the other, with no operations in between. In other words, it is guaranteed that

b,c, andd, emitted bya, will not be interleaved by other operations. This property holds true even ifais not the root of the call graph. - If you emit a sequence of operations, the whole sequence will be executed before any possible internal operations that may arise as a result of any of these operations.

Returning values

When trying to port an existing distributed application to Tezos, you may want to read the storage of another contract or call some entrypoint to get a computed value. In Tezos, entrypoints can only update storage and emit other operations.

In theory, one can use a callback – the callee could emit an operation back to the caller with the computed value. However, this pattern is often insecure:

- You should somehow make sure that the response matches the request. Due to the breadth-first order of execution, you cannot assume that there have been no other requests in between.

- Some contracts use

Tezos.get_sendervalue for authorisation. If a third-party contract can make a contract emit an operation, the dependent contracts may no longer be sure that the operation coming from the sender is indeed authorised by the sender.

Let us look at a simple access control contract with a "view" entrypoint:

Now imagine we want to control a contract with the following interface (we omit the full code of the contract for clarity; you can find it in the examples folder):

You may notice that we can abuse the IsWhitelisted entrypoint to pause and unpause the token, even if we are not among the whitelisted senders. Try it out:

tezos-client call "$ACCESS_CONTROLLER" from "$EVA" --entrypoint "%isWhitelisted" --arg "Pair ($WHITELISTED_ADDRESS, $TARGET %setPaused)"

Contract factories

So far, we have covered only one type of operation – transaction. But we can originate contracts from LIGO a well! There is a special instruction Tezos.create_contract. It accepts four arguments:

- Contract code. Note that the code must be an inline function that does not use any existing bindings.

- Optional delegate.

- The amount of Tez to send to the contract upon origination.

- The initial storage value.

For example, we can create a new counter contract with

Tezos.create_contract returns a pair of origination operation and the address of the new contract. Note that, at this stage, the contract has not been originated yet! That is why you cannot forge a transaction to the newly-created contract: Tezos.get_{contract, entrypoint}_opt would fail if called before the origination operation has been processed.

CreateAndCall contract in the examples folder shows how we can call the created contract with a callback mechanism:

By the time %callback is called, the create_op would be completed. Thus, the factory %callback can forge yet another operation to call the default entrypoint of the new contract:

| Current call | Queue before | Queue after |

|---|---|---|

A %createAndCall | [] | [Originate B, A %callback] |

Originate B | [A %callback] | [A %callback] |

A %callback | [] | [B %default] |

B %default | [] | [] |

If you use this pattern, please mind the execution model and check whether the guarantees it provides are enough for security of your application.